Specialists in the conservation and repair of traditional and listed buildings

Since Roman times Repointing historic brickwork stonework, the vast majority of historic buildings constructed in the UK with brick or stone would have been constructed with a mortar made of some form of lime and aggregate. Cement was only used from the 19th Century and then it would have been far weaker than the elements of today.

When producing a mortar for repointing historic brickwork stonework the following should always be taken into account.

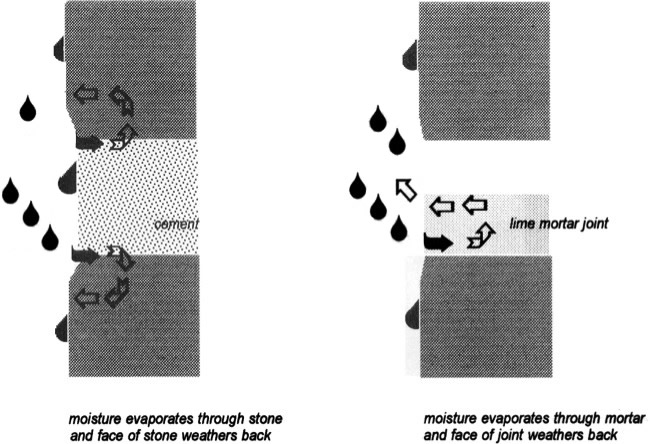

Cement mortar on the left will erode the masonry. Lime mortar on the right will allow the masonry to remain dry. After repointing historic brickwork stonework

Repointing is generally carried out if the existing mortar joint has recessed to such a degree that it is potentially going to cause (or is causing) the brick or the stone to decay or is allowing moisture to enter the building.

It’s important to work out why the mortar is decaying; whether it’s general erosion that is taking place over a long period of time or whether there has been a change to the building and its environment e.g. gutters have begun to leak or ground conditions.

Additionally earlier repointing in cement mortars can cause long term problems to a structure and it may be necessary to remove the cement mortar and repoint using a softer material.

Cement mortar stronger than the brick can lead to the brick decaying.

Inappropriate cement repointing on the left.

As mentioned above it might also be better to do nothing. If, for instance, a building is 100+ years old and the mortar joint has only recessed a few millimetres it may be better to leave it in place as the original mortar is probably performing well and to remove it and replace it with a new mortar could be a waste of money, cause long term damage to the building and if not carried out properly could leave the building looking unsightly.

Generally in the UK lime for building work has always been derived from chalk or other suitable limestones (although shells may have been used in some coastal areas). So mortars may vary depending on what materials were used and when and how it was produced.

Historically limestone would have been quarried locally and its chemical makeup could have varied from site to site; some limestones would have produced a feebly hydraulic lime. But generally the limestone used would have contained more than 90% calcium carbonate and would have relied on the carbonation process to provide a set. From the 19th Century as lime burning techniques improved other harder limestones containing reactive silica and alumina were able to be used. These produced a lime that produced a chemical set and today these are referred to as hydraulic limes.

So today lime for repointing can either be a non-hydraulic lime in the form of putty lime or a bagged hydraulic lime in varying strengths. The choice of the lime is dependent on individual projects.

The use of aggregates is sometimes underestimated in historic mortars. It’s not sufficient to just mix 3 parts of sand with lime and expect it to produce a mortar that will work. To produce a successful mortar for repointing the aggregates should match the original as closely as possible and be well graded, so as to enable the correct ratio between lime and aggregate.

Good lime repointing matching 18th Century brickwork.

Even if all the materials have been selected and a suitable mortar designed and produced, it is crucial that the contractor has a good understanding of working with historic mortars. This includes understanding the permeability of the structure, gauging the water content of the mortar correctly, being aware of the effects of weather and temperature on the mortar and how to make sure the pointing cures correctly. It is also vital for the craftsman to know how to compact and finish the mortar joint to achieve a matching mortar of a high standard.

The use of the correct tools is vital!